"Terracotta Gardu Palace" for Jatiwangi Art Factory

In July 2024, Jatiwangi Art Factory (JaF) organized the Tera Kota Triennale, a retrospective exhibition. Ginggi Syarif Hasyim and Arie Syarifuddin from JaF invited Collective Works, Olga Mink, and Godelieve Spaas to take part.

The group had previously worked together on a festival focused on economic ownership and arrived in Jatiwangi interested in how the community understands alternative economies. Today, Jatiwangi is home to large factories built by Korean, Chinese, and Taiwanese companies. These factories produce goods for brands such as Nike, Gucci, and H&M and are rapidly transforming the area. While Jatiwangi once had around 5000 residents, a single Nike factory now employs 10000 people. JaF raises the question of what happens when these factories leave and how the community might adapt.

What began as a conversation about alternative economies soon expanded into reflections on the position of the Dutch participants. Parallels emerged between the history of Dutch colonialism and the current influence of foreign companies, prompting questions about responsibility, distance, and involvement.

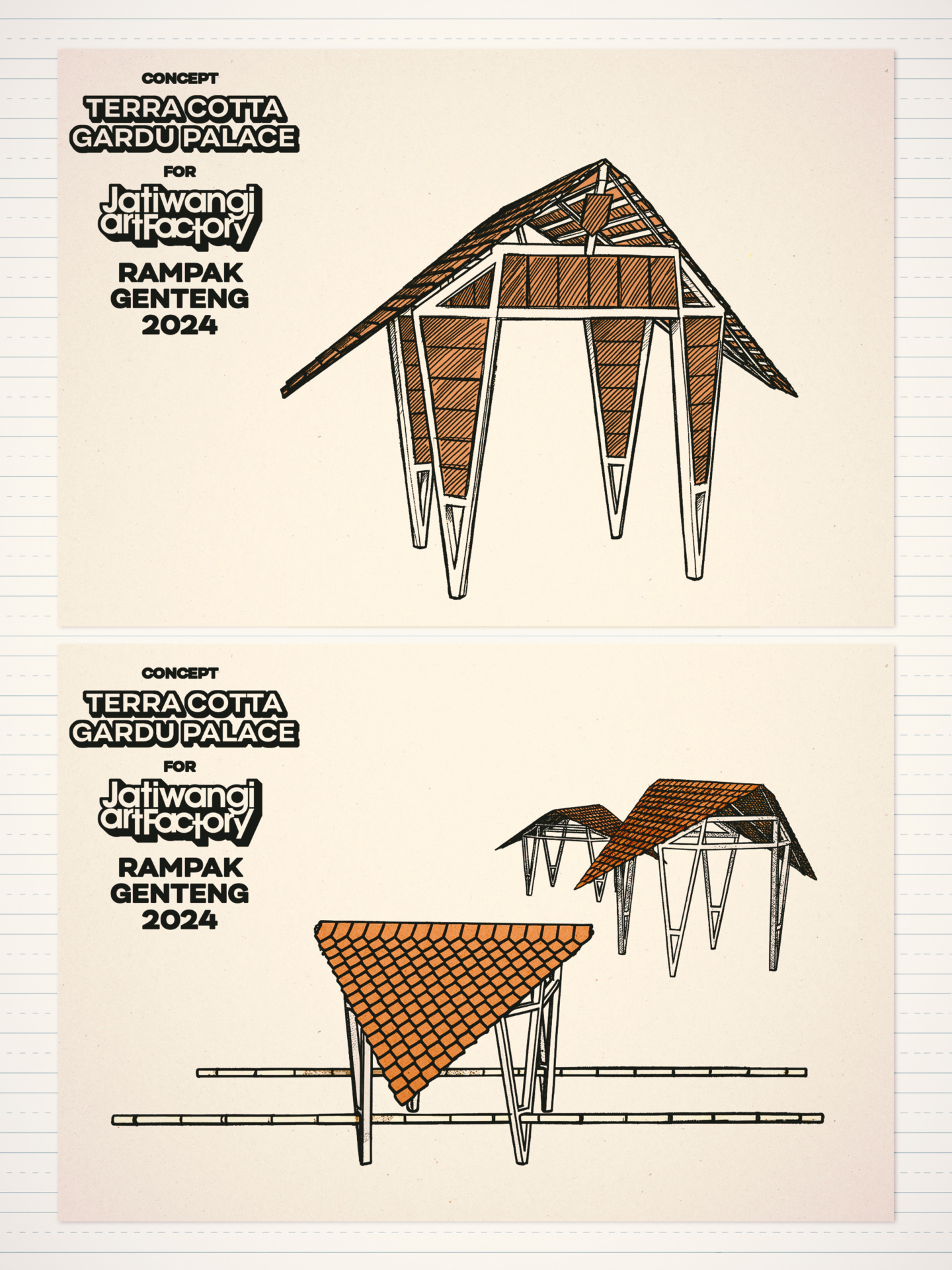

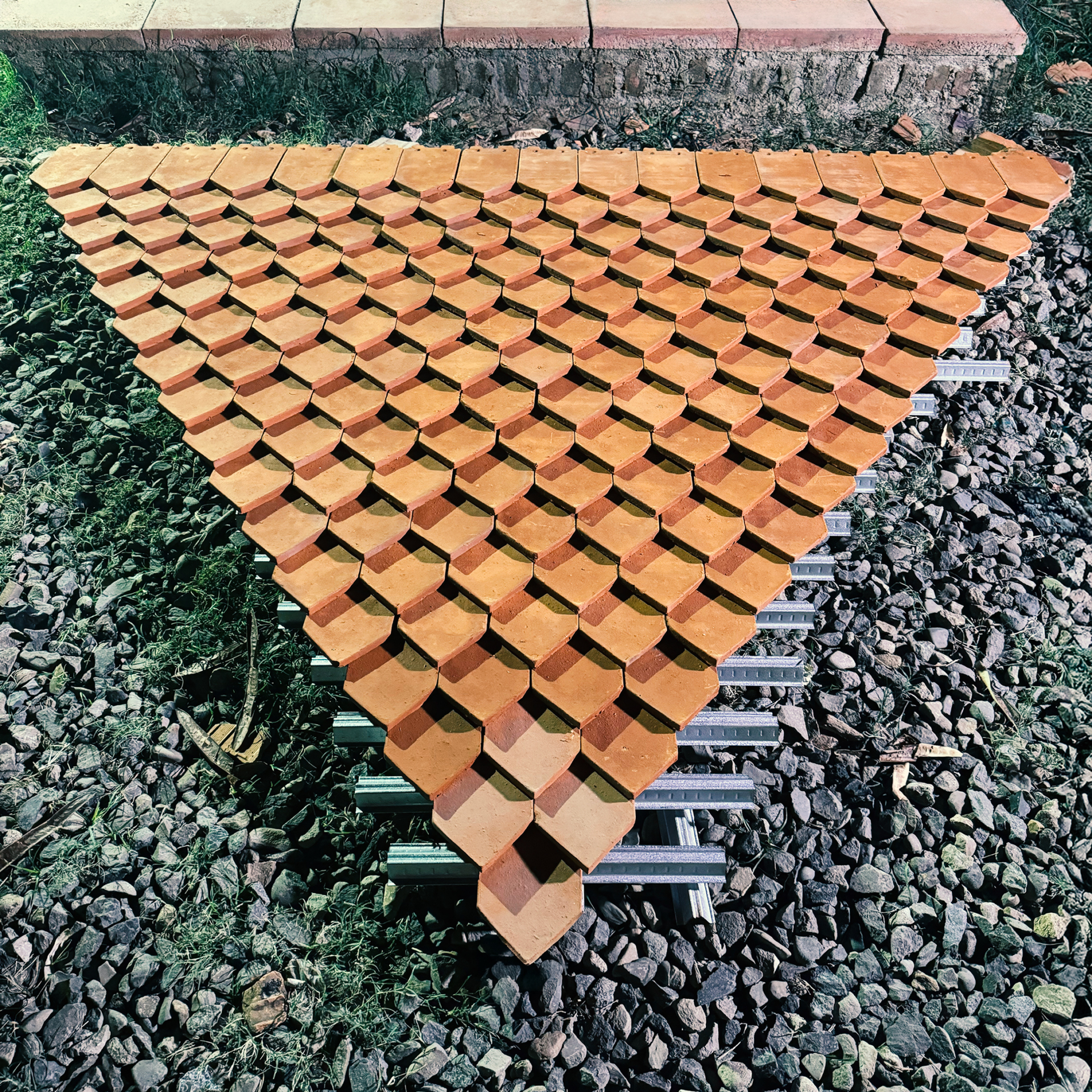

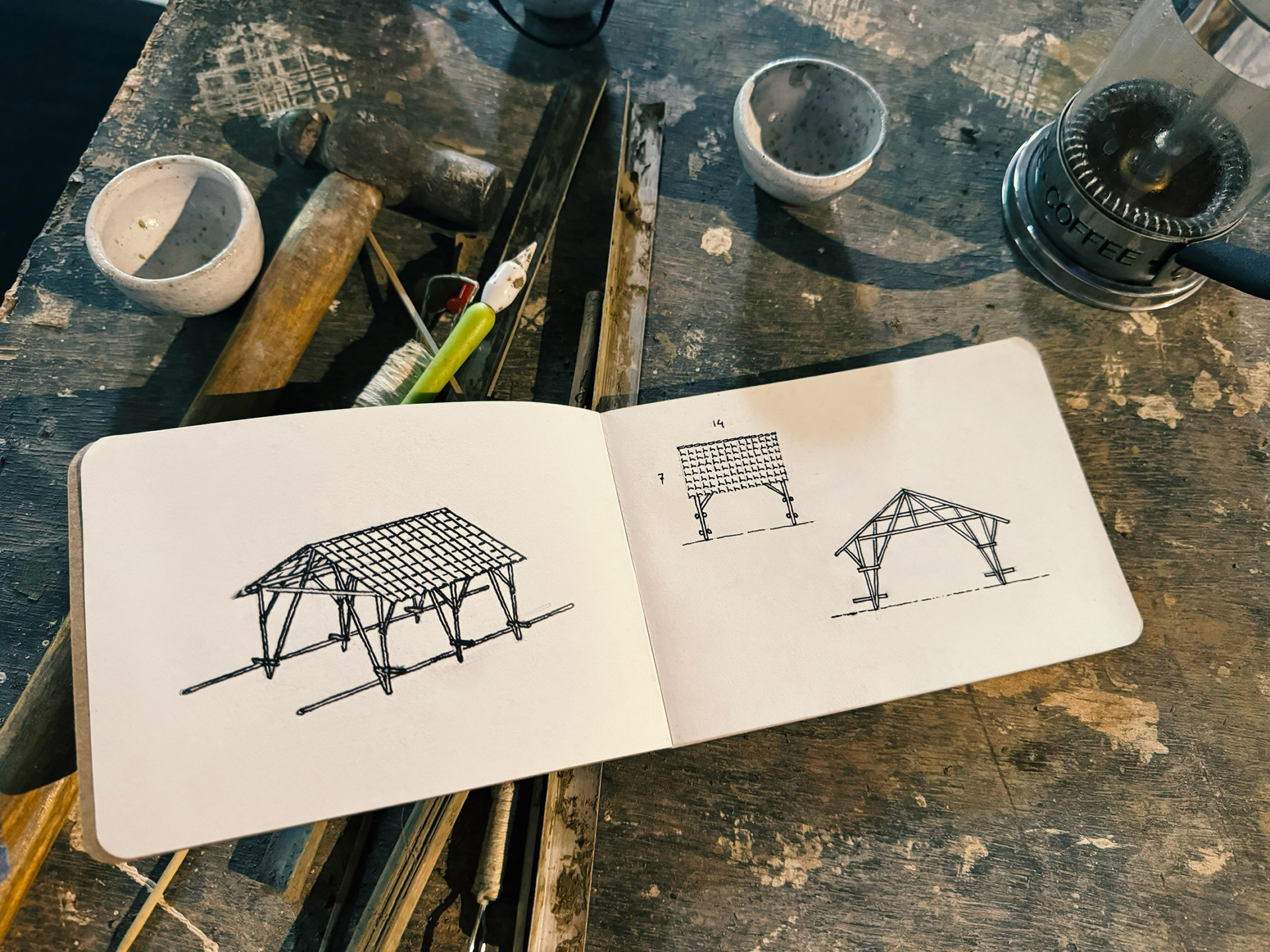

Collective Works proposed a mobile space for dialogue about land in the form of a small roof made from local roof tiles. It would offer a place to sit directly on the soil from which the tiles were produced. The structure was conceived as something that could be moved to areas being developed for factories, hotels, or housing, creating temporary settings for discussion about these changes.

Within Collective Works, this proposal related to earlier experiments with mobility, shared tools, and temporary structures developed through the Constructlab network.

The idea of a “wandering roof” connects to certain ideas that had previously been explored within the Constructlab network. Roofs bring shelter, shade, and a place for gathering. By moving them, people can come together to discuss ideas, adapting to different spaces and contexts. In the wider context of Constructlab’s work, mobility is key. They create mobile tools and machines that support community-based activities like cooking, woodworking, and even printing. These tools often also serve as archives of ideas, memories, and materials, creating flexible spaces such as agoras, kiosks, toolboxes, and display infrastructure.

This mobility allows Constructlab to support hands-on, collaborative projects in different places, encouraging people to engage with their surroundings. The adaptable nature of these tools illustrates how objects, people, and actions shape the spaces they inhabit, reinforcing a collective and flexible approach to community-driven change.

In Jatiwangi, these ideas were encountered alongside existing local practices rather than introduced as something entirely new. The group visited a roof tile factory and a project involving traditional Saung barns, community structures once used to store surplus crops and to gather. They also explored Gardu shelters. Originally built by migrant workers during colonial times, these small structures are still used today for resting and eating in the fields.

A key moment was a visit to a community that practices Gotong Rumah. During the Wakare Festival, residents carry miniature huts through the streets. This tradition began during relocations under Japanese occupation in 1942 and symbolizes solidarity and a shared relationship to land. Gotong Rumah demonstrates the power of collective movement, both physical and symbolic.

As the group learned more, questions emerged about whether a wandering roof was needed at all or whether it might overlap with existing traditions. Arie and Ginggi appreciated the proposal but suggested shifting the project to align more closely with JaF’s long term vision. They proposed placing the roof near the ruins of a Dutch sugar factory from the colonial period and leaving several roofs there after the upcoming Rampak Genteng festival. Rampak Genteng is a ritual in which roof tile instruments are played together as a collective statement. It has taken place every three years in Jatiwangi since 2012. The idea was to create a landmark that could continue to prompt conversations about the future beyond the Korean, Chinese, and Taiwanese factories.

Today, government land in Jatiwangi is being sold to South Koreans, Chinese, Taiwanese, and wealthy city dwellers, while locals can’t afford to buy it. Factories, malls, apartments, and hotels are replacing farmland. Factories have moved from central Jakarta to Jatiwangi since 2015/2018, and there’s a prediction they’ll move to Kalimantan next, and then Africa. Although foreign ownership is technically illegal in Indonesia, legal loopholes allow it, often with locals holding titles but not benefiting.

JaF is concerned that this development will cause the loss of local knowledge about the land, clay, and ceramics. They advocate for 30% of new buildings to use local materials to preserve these traditions. This approach aims to protect knowledge and resources for when the factories eventually leave.

At the Rampak Genteng festival JaF was planning to establish Terracotta City (Kota Terrakota). This initiative aims to influence urban planning from the ground up, ensuring that traditional building practices and local materials shape the future of the area after the factories leave.

In the final days of the visit, designs were refined and construction of a full scale prototype began. The structure was intended to serve as a Terracotta Gardu Palace during the festival. It would humorously mirror the role of Indonesia’s new government building in Kalimantan, which is shaped like an eagle. The smaller structure was imagined as a symbolic gathering place where residents of Jatiwangi could meet, talk, and work together. JaF considered constructing up to five of these structures.

JaF believes in the strength of local communities and sees the role of artists as key to rediscovering how to live together. As success is increasingly measured by economic rather than human values, JaF is concerned that vital connections to the land, food, and traditions like ceramics are being lost. They advocate for decision making that is grounded in real, tangible matters and includes all stakeholders.

JaF holds monthly open meetings that bring together local officials, artists, businesspeople, and community members. These meetings foster equal dialogue, allowing everyone to contribute to decisions. In the past, high ranking officials could be engaged as equals in Indonesia, but that is no longer the case. This makes it even more important to strengthen local, community driven governance.

The decision by the local crew to use metal for the basic structure raised concerns.Combined with the roof tiles, it was unclear whether the structure could still be carried. With little time left, however, the welding and installation of the locally produced tiles began.

In parallel, as a last act, a new coat of arms was developed to accompany the structure. Instead of the Garuda, Indonesia’s national symbol, the design evolved into a rooster, a figure associated with groundedness and resilience. The word gardu in Indonesian refers to a shelter or guard post. Its phonetic proximity to rooster allowed the symbol to function as a deliberate play on words, reflecting the idea of community led governance.

With the structure half completed, it was time to leave. The intention was to return and continue working on the project. The concept would be refined further, with attention given to integrating local traditions and skills, responding to rapid industrialization, exploring alternative land use and ownership models, and preserving traditional crafts.

Gotong Royong is a key concept in Indonesian culture, meaning “mutual assistance.” It involves people working together to support one another and share responsibilities within their community. This tradition can be seen in activities like cleaning up the environment or helping neighbors during important events. A unique aspect of Gotong Royong is the collective moving of entire houses, showing deep communal cooperation and flexibility. This practice emphasizes that support given to others will be returned in the future, building strong community bonds and a sense of shared responsibility. This approach resonates with the idea of “wandering roofs,” offering flexible and collaborative solutions for community spaces.

In reality, no next steps were taken. The Rampak Genteng festival was approaching, attention shifted, and the project gradually moved out of view. It also became clear that the metal structure, combined with the roof tiles, was too heavy to be carried. The wandering roof never moved. The roof elements were eventually reused to build terracotta landmarks instead. It is what it is. Sometimes projects take this course.

Although the Terracotta Gardu Palace never fully came to fruition, the process opened up many relevant conversations. It raised questions about land ownership, industrial expansion, local knowledge, material traditions, and community led governance. For that reason, the project retains value as a shared moment of inquiry and exchange.